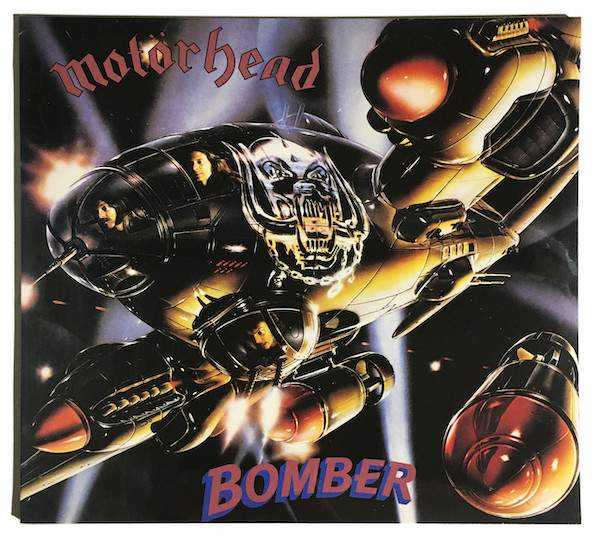

War? What is it good for? Well, where would the military-industrial complex and manufacturers of model kits be without it? In 2019, the kit maker Airfix released an unusual new line – a Motörhead Heinkel He 111 bomber, a scale model to mark the 40th anniversary of the release of Motörhead’s Bomber album. On the album sleeve, Motörhead’s three Luftröckers look out from inside a literal manifestation of heavy metal. They form the crew in a Heinkel 111, the largest of the Nazi bombers that regularly blasted British cities during the Blitz. Your correspondent was 15 when Bomber was released. For me, this album’s sleeve and title track are fascinating artefacts that sit on the juncture between rock and war.

Warfare and loud music have frequently intersected. It’s a tandem that’s been ridden by amplified music-makers as varied as Iron Maiden, Einstürzende Neubauten, Public Enemy, Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark, Billy Childish, the Prodigy and Public Service Broadcasting. Arguably, war has conjoined with rock music for longer than rock music has existed. Brass-laden military bands could be seen as a kind of heavy metal before the fact. Warfare has blended with musical loudness across the ages, from rams’ horns bringing down the Walls Of Jericho in the Old Testament to Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony of 1942. The stage cannons in Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture were echoed when similar artillery augmented the power chords of AC/DC’s ‘For Those About To Rock (We Salute You)’. Among those who are always about to rock, Iron Maiden have sung of war with particular regularity.

Truth to tell, I never owned a Maiden album as a kid. As Motörhead’s Bomber album was released, my own music tastes were modulating. My adolescent amazement at the virtuoso hard rock of Queen, Rush and Rainbow was being augmented by the occasional punk single: The Sex Pistols’ ‘Holidays In The Sun’, The Clash’s ‘Tommy Gun’. My post-metal purchases were sometimes gauche, devoid of retrospective cool. The first “punk” album I bought was The Boomtown Rats’ A Tonic For The Troops. Troops? Perhaps my enthusiasm for this nod to soldiering was somehow part of a bigger picture. My father had served in the Second World War, volunteering in 1942 on his 18th birthday. The pocket-size Commando comics had been a staple of my childhood, with titles like Revenge Of The Gestapo, Hell In A Hellcat, Escape From Java, and on and on…

The Tonic For The Troops album has a track called ‘(I Never Loved) Eva Braun’. Here was more Second World War content, but in this case more about quizzical provocation than battlefield drama. For me, the Rats were a transitional way station en route to more resonant post-punk variations – to bands including Joy Division, a group whose name is maybe the ultimate in rock/war gravity. But, as I abandoned hard rock for post-punk, Motörhead seemed inviolable, beyond musical boundaries. When ‘Ace Of Spades’ blasted out in our school common room, it was never met by the factional derision that could greet, say, Genesis or Cabaret Voltaire. Motörhead played on. The Bomber sleeve lodged, ineradicable, in my brain.

In 2001, Q magazine made me a co-editor of a kind of one-off rock summer special: THE 100 BEST RECORD COVERS OF ALL TIME. The Beatles, Bowie, Led Zeppelin, Kate Bush – they all featured. But, for me and my fellow editors, Ian Harrison and Paul Stokes, the main editorial agenda was easing in as many unlikely cult-ish choices as possible: Earl Brutus, Add N To (X), Half Man Half Biscuit, the album Doin Thangs by Big Bear. There was, of course, also room for Motörhead’s Bomber.

Lemmy was interviewed for the album-sleeves book, talking about the Bomber cover: “I insisted it should be a German plane. Sure, it’s a filthy memory, but the fact is the bad guys made the best shit. The Spitfire was a very beautiful aircraft, but Messerschmitts looked like they were built to kill.” Motörhead were all about careening, white-line abandon, but the Bomber sleeve was created with rigour and research. The RAF Museum at Hendon, home to an actual Heinkel III, provided reference material. Illustr…