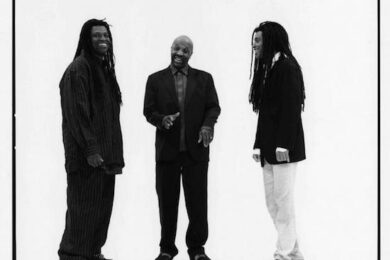

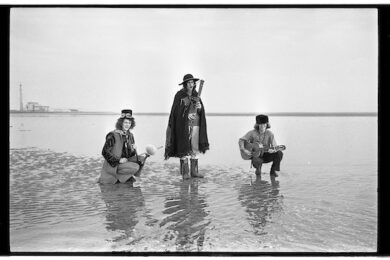

Julian Cope at Silbury Hill, Wiltshire by Cat Stevens. All other photographs courtesy of Adelle Stripe

This article was the first essay written exclusively for our Quietus subscribers and is being made public to give a taster of what you get (alongside exclusive music, podcasts, playlists and a newsletter) as a Low Culture or Sound & Vision tier member. To find out more about these perks go here and to get your first month’s subscription free visit our page on Steady to sign up

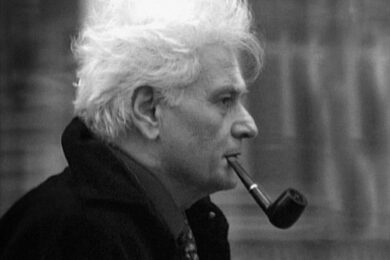

The first literary event I ever attended was a date on The Modern Antiquarian book tour at Leeds Waterstones in 1998. Having been to countless since, I can confirm that it was the finest, and therefore the Ur-reading against which all others will be judged. It helped that the author, Julian Cope, was a bona fide popstar who was quite happy to stand up in front of an audience and ad-lib his way through 60 minutes of discussion about stone circles, which was the subject of his new book. He marched into the room wearing a leopard-print hat, matching fake-fur coat, juggler leggings, big sunglasses and a pair of enormous platform boots that took his height to approximately 7ft 6in. It was an outfit that clearly meant business. At the time, I had scant knowledge of the strange pagan world that was the object of his obsession. This had culminated in him spending most of the previous eight years traipsing around windy landscapes creating this new guide to the forgotten megalithic sites of Britain that were first constructed in the late Neolithic period.

His voice was rich, velvety and ever so slightly posh; Cope was unlike anyone I had ever seen or heard before. In the grim meat-and-potatoes land of late-90s fashion, he looked like he had landed from outer space. And not in a contrived way either, though truth be told he did look like a bit of a berk. What he said that night connected with me on a superficial level. Why would we travel halfway around the world to visit the Nazca Lines or Chichén Itzá, when there were equal treasures on our doorstep, he asked. Easy for you to say that, I thought to myself, when I could barely afford the bus fare into town that night, never mind a trip to the Isle of Lewis to look at some old stones. However, my interest was piqued, as I had recently devoured a copy of Head-On and thought perhaps there was something of interest in what the Arch Drude had to say. According to Cope, Avebury, in the Marlborough Downs, was as culturally significant as The Stooges, which gave me cause to investigate his claims further, and even now, 22 years later, I am still chipping away at this idea.

Now, for the sake of this story, I’m going to say that I bought a copy of the book that night, priced £29.99, and that Julian signed it for me afterwards (embrace the myth!). The reality is it was far too expensive on a H&M-fitting-room wage, so it would be another year or two before the hallowed tome finally made its way into my possession. My copy is scratched, a bit faded, and a little grubby on the corners. I have been dragging the damned thing around muddy fields for two decades, convinced that the book itself has some mystical significance. It has witnessed arguments on Dartmoor, epiphanies at Castlerigg, first dates at West Kennet, grief at Arbor Low, blowjobs on Silbury Hill, and perhaps, most recently, the end of lockdown at Sunkenkirk, where visitors squirted antibacterial gel on their hands after touching its quartz-veined stones. Since its acquisition, I have visited a paltry 22 of the 300 sites in the book, which isn’t too bad going considering I am incapable of driving. Julian faced the same predicament and didn’t learn to drive until he was 34, at which point he realised he was no longer prepared to rely on others to cart him around the country, and from then on his journey of discovery of megalithic Britain began.

Tellingly, an image of Callanish’s cruciform shape was used on the cover of his 1992 album Jehovahkill and marks the beginning of Cope’s Modern Antiquarian period. Prior to its recording, he was depressed, and in his “Paul Weller phase, composing music that I felt nobody was getting”. Writing in The Sunday Times, Cope recalls that when his friend Pete de Freitas of Echo And The Bunnymen died, he was overwhelmed with grief and visited Avebury, which provided a sense of calm and “inspired a lunatic awe”. In the following years he decamped there and brought up his family in the area, where he was jokingly referred to by Coil’s John Balance as Lord Yatesbury. As one of his personal heroes, Gurdjieff, once wrote: “Awakening begins when a man realises that he is going nowhere and does not know where to go.” It was at this uncertain point in his life that Cope transformed himself from a popstar into a serious researcher of ancient history and created what would become one of the most important contributi…